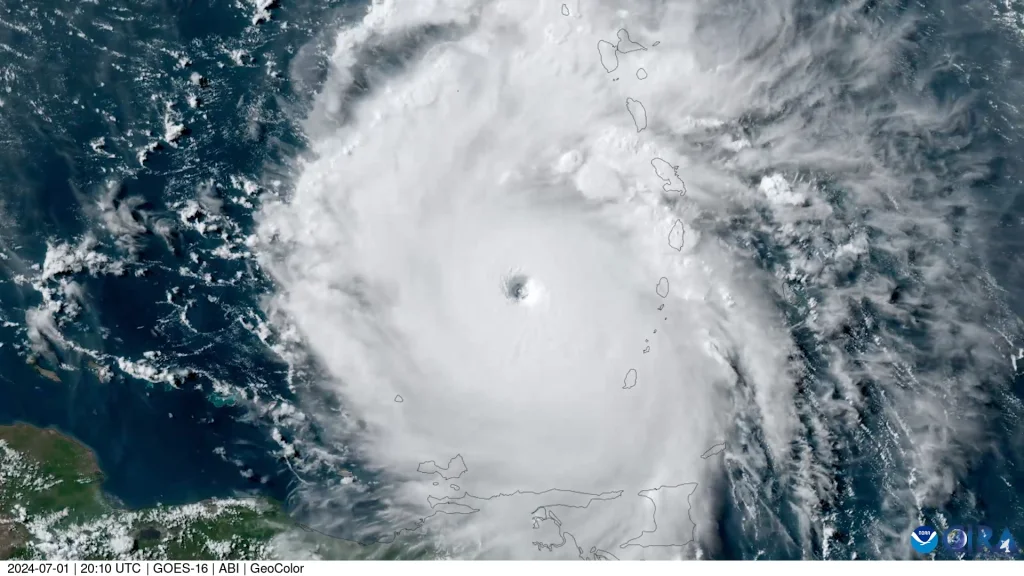

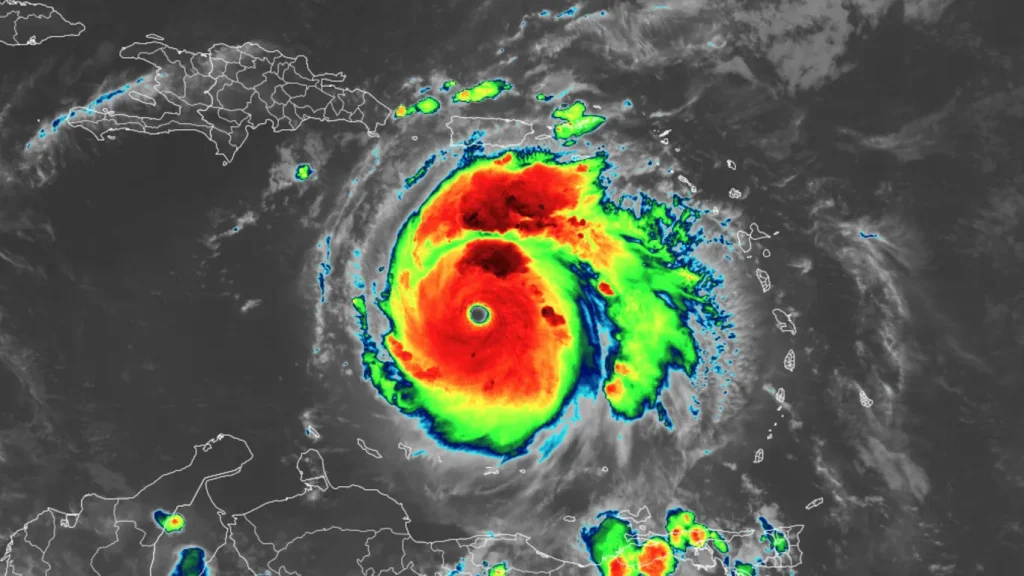

As hurricane season commences this month, a forecast by NOAA at the end of May predicts an above-normal season with 17 to 25 named storms expected between June 1 and November 30. According to NOAA, “The upcoming Atlantic hurricane season is expected to have above-normal activity due to a confluence of factors, including near-record warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean, development of La Nina conditions in the Pacific, reduced Atlantic trade winds, and less wind shear, all of which tend to favor tropical storm formation.” Barely three weeks into the season, Tropical Storm Alberto has already wreaked havoc in Mexico and parts of Texas, bringing torrential rain and flooding.

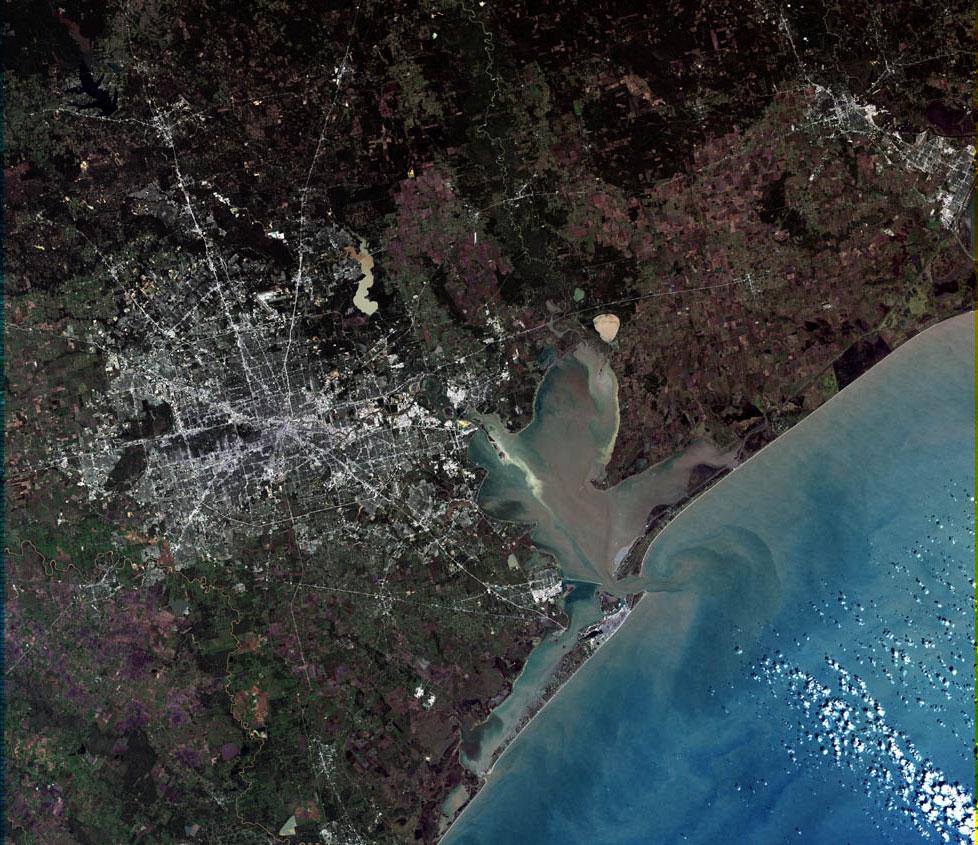

With the emergence of Hurricane Beryl, many are concerned about the potential impact on natural gas prices. Historically, significant hurricane activity in the Gulf of Mexico had a major influence on natural gas prices. During the 1990s, energy traders closely monitored hurricane developments as powerful storms approaching the Gulf of Mexico’s production regions (from Corpus Christi, TX to Mobile, AL) would necessitate the evacuation of drilling and production platforms.

This evacuation often led to a substantial reduction in natural gas production, sometimes lasting a week or more if the platforms sustained severe damage. The highest natural gas prices in the last thirty years were recorded in the aftermath of Hurricanes Rita and Katrina in 2005, both of which caused major disruptions in production and supply.

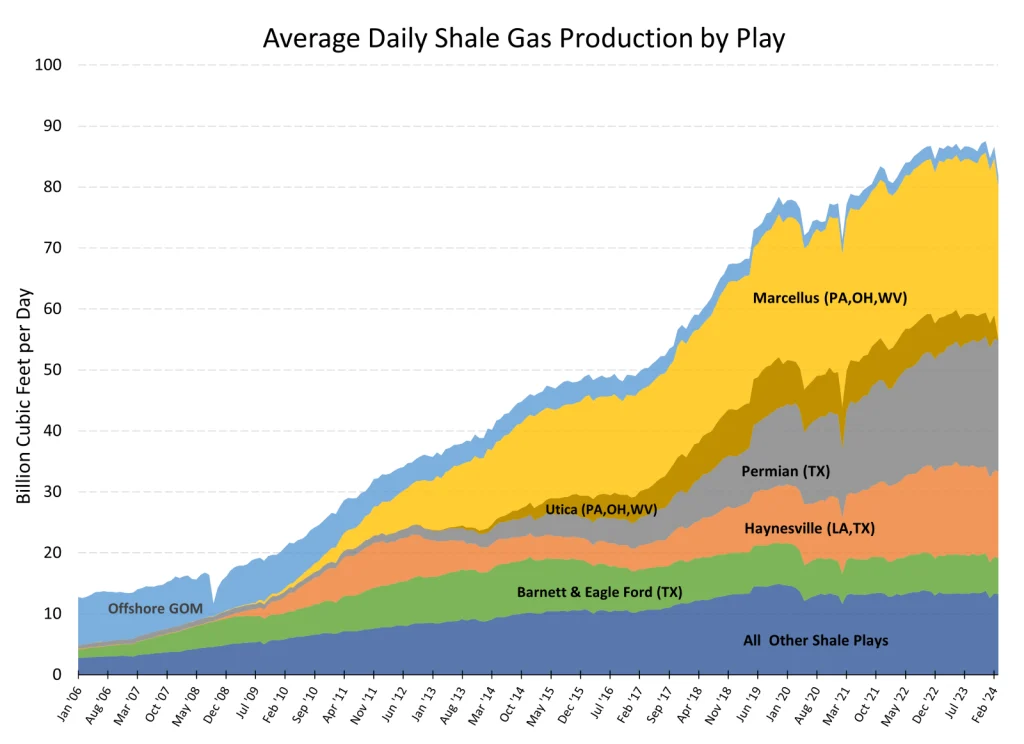

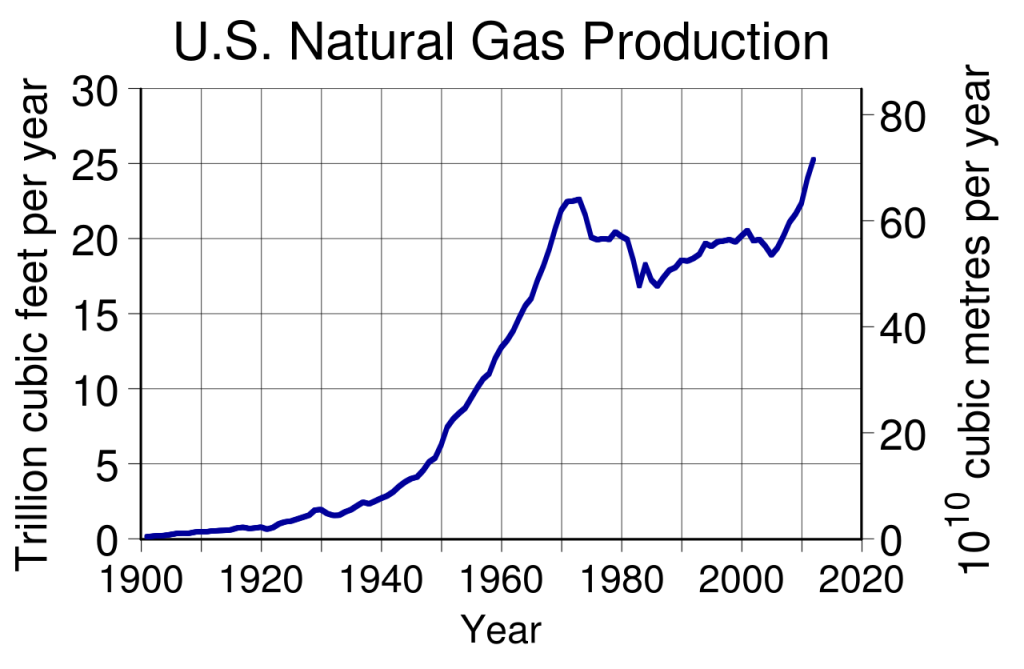

However, the dynamics have shifted considerably in the past two decades. The advent of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has unlocked major onshore shale reserves, reducing reliance on offshore production. Natural gas extraction from the Marcellus and Utica shale formations in the Appalachian Region, along with other significant reserves across Texas, now outpaces production from offshore platforms. In January 2006, offshore platforms in the Gulf of Mexico were the primary sources of natural gas. By 2010, onshore supplies from formations like Utica, Marcellus, Permian, Haynesville, and Barnett/Eagle Ford became the dominant sources of domestic natural gas.

Interestingly, major hurricanes today are more likely to exert downward pressure on energy prices. This shift is due to the decreased energy demand immediately following a major storm.

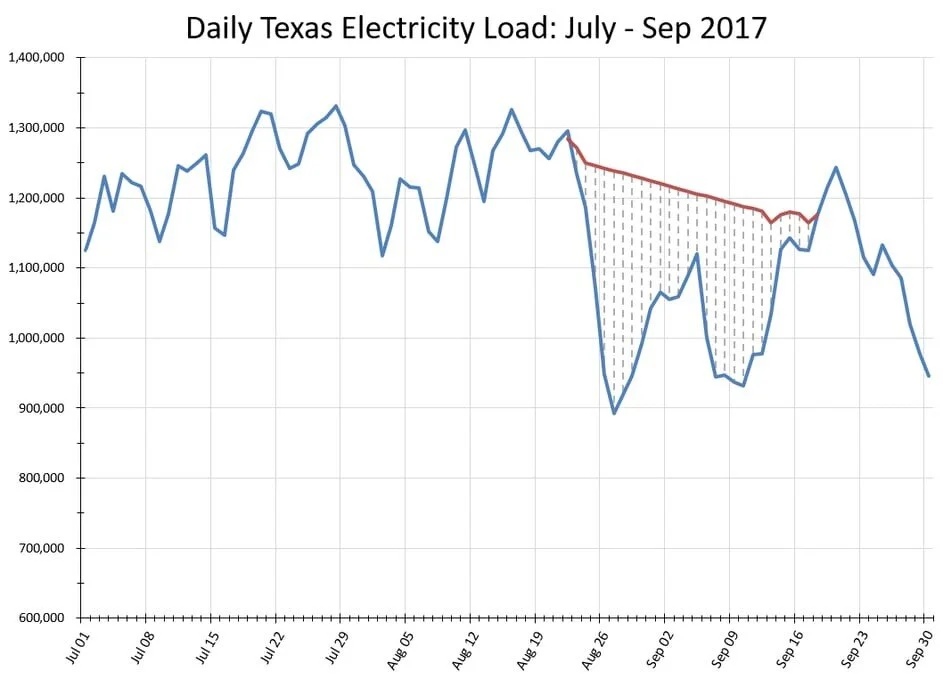

For example, Hurricane Harvey, which struck the Texas coast on August 25, 2017, caused a notable drop in electricity usage. Prior to Harvey’s landfall, Texas used about 1.25 million MWh of electricity per day. Two days post-landfall, this usage dropped by nearly 30% to 900,000 MWh per day, correlating to a significant reduction in natural gas consumption needed for electricity production.

The aftermath of Harvey saw a reduction in electricity usage over the following 3.5 weeks, amounting to approximately 35 Bcf of natural gas that was not consumed in Texas alone. As Harvey degraded into a tropical storm and moved across the country, it continued to dampen electricity usage and natural gas demand.

Given that the majority of domestic natural gas now comes from onshore reserves, the decrease in demand following a storm like Beryl is more pronounced than any reduction in production from the Gulf of Mexico. Therefore, a significant hurricane is more likely to reduce electricity demand than to disrupt natural gas supply. This dynamic implies that in today’s context, a large disruptive hurricane will likely be bearish for natural gas prices due to the combination of abundant onshore shale reserves and the anticipated reduction in demand post-storm.

As Hurricane Beryl approaches, the industry will be closely watching its path and impact. However, based on current trends and the shift in natural gas production dynamics, it is anticipated that any significant storms this season, including Beryl, will more likely lead to a decrease rather than an increase in natural gas prices. How times have changed.